Joseph Campbell was a writer who identified a structure common to many myths that he named the hero’s journey. You can use Joseph Campbell’s mythology to structure your own fiction regardless of the genre or type of story you want to tell.

Campbell combined his knowledge of myth and religion with modern-day psychology to arrive at his version of the hero’s journey. By drawing on psychologists including Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, Campbell ensured that his structure had emotional resonance as well.

Perhaps the most famous example of the use of the hero’s journey in pop culture is the series of Star Wars movies, and their creator, George Lucas, has spoken at length over the years about his use of the mythic structure. However, the structure can be seen in the work of many novelists as well including J.K. Rowling.

Writers examining the hero’s journey as a way to structure their own novels should keep in mind that not every single myth includes every stage of the hero’s journey, and sometimes the stages occur in a different order. The basic structure developed by Campbell can be altered by writers as necessary for the story and still remain effective. Similarly, even though Campbell called the structure the hero’s journey, heroines can take the same journey as well.

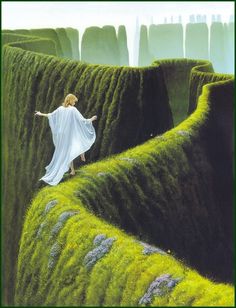

In full, Campbell’s journey has 17 stages that can be divided into three parts: separation, initiation and return. The journey usually begins in the ordinary world; this is the mundane existence the hero or heroine is living before the first thrilling stage yanks the character out of complacency.

Separation

- The Call to Adventure – This is the first incident in the story that incites the protagonist to consider some kind of action. In myth, this might be the first mention of the minotaur to the hero Theseus. In a romance novel, this might be the heroine’s first glimpse of and attraction to the man she will fall in love with. In a mystery, the protagonist might first learn of the crime.

- Refusal of the Call – When the protagonist makes this refusal, it creates conflict within the story. Initially, the instinct of the romance heroine might be to decide that the man is trouble. The budding detective may think she is unprepared to tackle a murder case.

- Supernatural Aid – Myth is full of supernatural events, and in a fantasy story, the protagonist may be given a magic spell, a message from the gods or a talisman. However, the concept of supernatural aid can be adapted to other genres as well. In a novel with no supernatural elements, this can be aid from a mentor or a piece of valuable knowledge.

- Crossing the Threshold – Here, the character crosses the point of no return. Writers who are conversant with the Three-Act Structure may recognise this and the following step as similar to the reversal that occurs at the end of Act One. In the mystery, the detective takes an irrevocable step toward solving a crime. A romance novel protagonist may declare her feelings for the object of her affections.

- Belly of the Whale – Like Jonah in the Biblical story, the protagonist who crossed the threshold in the previous stage now truly cannot turn back. The hero might be prevented from doing so by outside sources. Perhaps the characters in a murder mystery find they are snowed in at the country house where someone has died.

Initiation

- The Road of Trials – The protagonist begins to encounter a series of trials. This stage may actually occur throughout this entire section

rather than at the beginning as the character solves or fails to solve an ever-complicating series of problems.

rather than at the beginning as the character solves or fails to solve an ever-complicating series of problems. - The Meeting with the Goddess or Mentor – This can be a meeting with any figure who has a kind of all-encompassing wisdom to offer to the character. In a realistic novel, this might be a work mentor or someone else the protagonist can look up to.

- Temptation – Campbell envisioned this as feminine, but it can be anything that threatens to lure the protagonist off the path. In a fantasy novel, this may be actual temptation toward the dark side. In a romance novel, the protagonist may be tempted by other life circumstances to abandon the romance.

- Atonement – Campbell wrote about this as atonement with a father figure, but again, this can be represented by any figure who has a great deal of power over the protagonist. This may be at the middle of the novel and may psychologically represent its ultimate conflict.

- Apotheosis – The protagonist must be willing to face a kind of death or annihilation. This will differ depending on the type of novel it is; the protagonist of a thriller races headlong into danger while in a piece of literary fiction, the character may consider abandoning a set of cherished ideals.

- The Ultimate Boon – If the novel is viewed as a type of quest, this is the moment when the protagonist succeeds.

Return

- Refusal of the Return – Sometimes, the protagonist may hesitate to return to ordinary life. This may particularly be true if it means leaving the place that the protagonist has experienced as a kind of enchanted realm.

- The Magic Flight – The protagonist may also have to flee, or this may simply be the story of the hero’s return. For example, a cop who has been undercover leaves the infiltrated group; this might be dangerous or emotional for that character.

- Rescue from Without – Even heroes need to be rescued sometimes. This could be a physical rescue or an emotional rescue depending on the type of novel.

- The Return Threshold – The protagonist may struggle with the return to the “real world” and the integration of what was learned with that return. For example, in a mystery novel, this may represent a struggle to convince others of the solution to the crime.

- Master of Two Worlds – In myth, the hero becomes a kind of saviour at this point. A more human approach might be showing how the character has grown and changed as a result of the events of the novel.

- Freedom to Live – This stage may be better suited to epic storytelling or epic fantasy fiction than other types of contemporary fiction as some novels may omit this final stage altogether. The hero achieves a kind of mastery and is able to pass wisdom on to others.

Keep in mind that some of these stages may be combined and others may not fit the genre of novel that you are writing or the story that you are trying to tell, but don’t be too quick to dismiss any stage. You may find that after thinking more deeply about a certain stage, it can add a dimension to your novel that you may not have considered. Used in conjunction with the narrative arc these formats will help you understand the best structure for your story.

Have you started plotting your novel yet? Go here to start fleshing out the detail of your story.

5 replies on “Joseph Campbell’s mythology: How to structure your story”

I have read a The Hero with a thousand Faces, book in which Campbell makes reference to these phases or stages the main character supposedly goes through aiming to become an hero. Your post is excellent and I thank you for proposing this interesting and dynamic read and use !!!!. Best wishes. Aquileana 😀

Thanks so much Aquileana, glad you enjoyed it 🙂

I wrote my capstone honors thesis about this. I compared ancient hero narratives like Beowulf and Gilgamesh to Harry potter and Star Wars using not only Campbell’s work but also Jungian principles of Archetypes. I also found something interesting that each narrative has beside Archetypal Heroic Patterns

Sounds fascinating, Franchesca. What was the other interesting thing you found?

Two years late to the party, but I would also like to know!